When it comes to sustainability, talented volunteers at the SIRCH Repair Cafe live the principles of reduce, reuse, repurpose and recycle every month — at events running April to October. The final cafe runs Sunday October 5th from 10 a.m. to 2 p.m. at the SIRCH Bistro in Haliburton. Feel free to drop by with items needing repair, have a coffee and snack, and speak with our fixers! This article gives a glimpse of a day in the life of the SIRCH Repair Cafe.

Caleigh arrives at the SIRCH Repair Cafe holding two broken radios. She’s reluctant to toss them out — especially the one that belonged to her grandmother.

Caleigh, who runs a gardening business in the area, checks in at the reception desk and completes a form for each radio. On a sunny Sunday morning, it’s quiet so far. After a short wait, Caleigh is escorted to meet two volunteer fixers.

Gary has a look at her smaller radio — it’s a retro-vintage model Caleigh picked up at a yard sale a few years ago. With his background in computers and electronics, Gary tests the radio and quickly determines that a dusty tuner knob is generating static. He takes apart the knob, cleans and lubricates it. Then he powers up the radio again and finds a nice, clear signal on a local FM channel — a DJ is introducing the next song.

Fixed!

But the next repair is trickier — volunteer fixer Jurgen has been looking at the larger radio. It’s an old AM/FM model with stereo sound. Jurgen and Gary open up the unit, conduct several tests, and confirm that one of the two speakers needs to be replaced.

The radio — a keepsake from Caleigh’s Grandma — can still be repaired, but Caleigh has some homework. She will look for a new speaker and aim to visit the next repair cafe to have it installed. Jurgen and Gary provide the specifications for the speaker including the required OHMs (electrical resistance units).

It’s another day in the life of the SIRCH Repair Cafe…

With its sustainability mandate and skilled volunteers — fixing everything from small appliances to electronics to jewelry — the SIRCH Repair Cafe is running seven events in 2025. Five of them are held at the SIRCH Bistro in Haliburton, and two here at the community centre in neighbouring Minden.

After a quiet first half-hour, there’s a buzz in the air now as more guests arrive with items to be fixed. Volunteer fixer Dave has unpacked his bicycle tools and is testing the “true” of a bike wheel. He’s removed it from the bike and connected it to his truing stand to check the side-to-side and vertical movement. Gary, a local musician, obtained the Raleigh bike from a friend. He enjoys riding it but noticed a thumping in the back wheel.

Dave makes some adjustments to the wheel’s spokes to make it straighter, and also re-seats the tire and tube. He reinstalls the wheel on Gary’s bike.

Back in business! A SIRCH volunteer rings a bell to celebrate another successful repair.

Across the room, fixer Rick tackles an unusual repair — a broken fishing rod belonging to a ceramic Japanese fisherman. The fisherman’s owner, Elisabeth, obtained the whimsical piece from the SIRCH Thrift Warehouse in Haliburton. She realized it would go perfectly with her collection of Bonsai collection.

Rick uses some fast-acting glue to repair the rod, and carefully rethreads the tiny fishing line and lure.

Hook, line and sinker — it’s fixed!

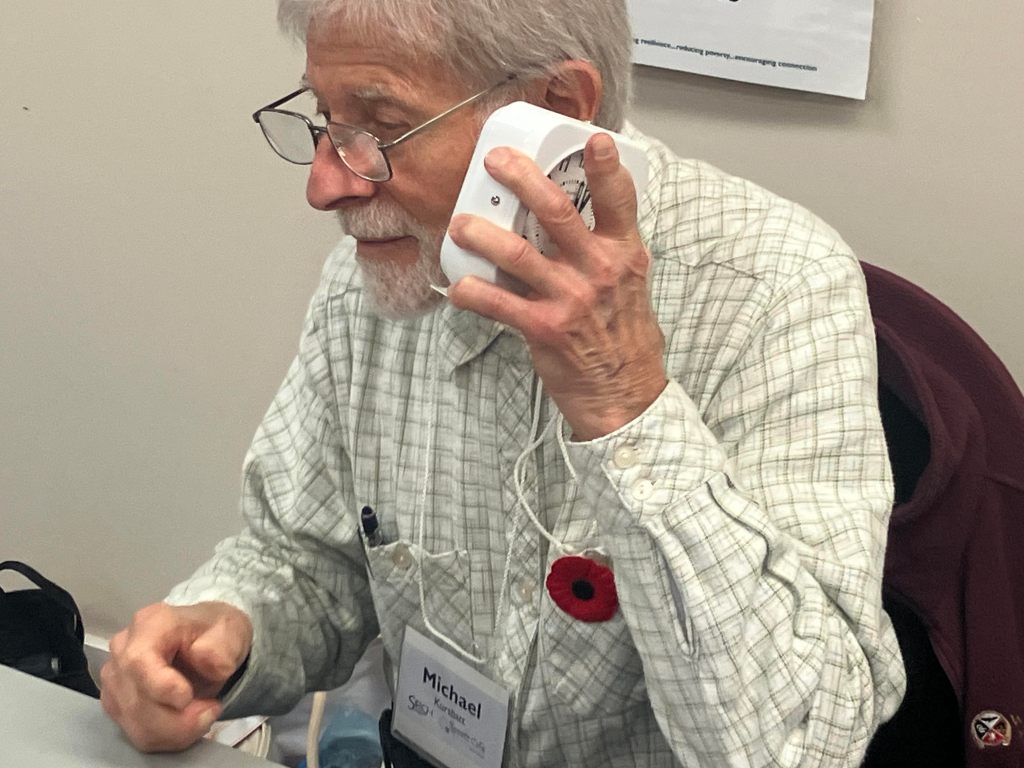

During a pause for lunch, we sit down with volunteer Barry, who’s working the reception desk with his fellow volunteers Gayle (left) and Laurie (right). Barry tallies up the day’s repair forms and reports that 30 guests have brought in 37 items so far.

A former auto mechanic and StatsCan field interviewer and supervisor, Barry doesn’t carry out repairs himself but uses his people skills to welcome and register guests at the Repair Cafe. He wants to establish trust and a comfort level with each guest, and to help triage the items that come in. (Most items, but not all, can be fixed). His day here actually started yesterday, with some prep work to bring materials and signage over to the Minden location.

Barry says the sustainability message — keeping things out of the landfill — resonates with most guests. But that message is further enriched by each guest’s role in the repair of their item. “We want the guest to be part of the repair, to meet the fixer, give some background, sit with them, learn about their item and any parts that might be required.” In a throw-away culture, “it’s important for all of us to know that most things can be repaired.” says Barry.

“So far this year we’ve repaired 170 items,” says Program Coordinator Dianne Woodcock. “Our success at keeping items out of the landfill hovers around 82% of all items brought in.”

Since the program restarted after the pandemic, it is closing in on 700 successful repairs, she notes. Guests have the option of donating to support the good works of SIRCH Community Services.

Did you know? Waste Reduction Week in Canada takes place during the third week of October. “We’re proud to be living the principles of Waste Reduction Week — reduce, reuse, repurpose and recycle — at every single Repair Cafe,” says Dianne.

Another loyal Repair Cafe fixer is Henry. A master jeweler and goldsmith, he first apprenticed in his trade in the 1950s. He’s still at it today, repairing an assortment of rings, bracelets and other jewelry brought in by guests at the SIRCH Repair Cafe. Henry dons his jewelers glasses to get a close look at each item, and to make expert repairs.

At the table to his right, Sue has been tackling a hooked rug featuring the face of a lion. It’s a two-stage repair involving some handwork to remove loose material, then her sewing machine to repair the frame of the piece.

As the clock ticks towards the 2 p.m. closing time, the Repair Cafe’s volunteers start packing up.

Today, they’ve repaired an amazing variety of items ranging from an electric sander to stereo equipment, bikes to bracelets, jeans to ceramics. Not to mention a soda machine. Along the way they’ve helped guests hang on to items of functional and often sentimental value. They’ll be back on the first Sunday of October in Haliburton, at the SIRCH Bistro.

Toss it? No way!

For more information on SIRCH Community Services and its amazing Repair Cafe, please visit: sirch.on.ca