Around 2007, my father-in-law Claus was under the gun to squeeze even more grandkids into the little log cabin he had completed in 1998.

Claus and Ann were lifelong learners, enjoying courses at Haliburton’s School for the Arts in summer. Ann honed her pottery and art skills, while Claus learned about the fine art of woodworking — including a course specializing in the use of the router.

Another course that caught Claus’s eye was memoir writing. During that one-week course, he told stories about his childhood in Manitoba, school days, his volunteer work in Africa — and about the little problem he was having fitting all the grandkids into the log cabin.

The title and story are his original; I have added a few subheads and photos. I would add an editor’s note: I recall Claus joking that there was sometimes an excess of emotion when his memoir-writing classmates read their stories — tissues had to be close at hand. Claus, by comparison, shared stories of his life and family with his own sense of humour, and carefully crafted details, without shedding a tear. The emotion — his love of family and pride in his craft — was implicit.

Here is the story he titled: “Cramming them in…”

By Claus Wirsig:

While large and rambling, our log cottage has only two bedrooms and a bunkie. Though a huge living room also lends itself well to accommodation of a pullout double or twin bed in one corer, the growing family size signalled trouble ahead.

All four of our daughters, scattered across the continent, wanted to gather at the cottage for their annual get-togethers. There were also friends to accommodate and the two oldest, Denise and Nadine, were married and already had three children between them. The first grandchildren were aged four and two in the summer of 1996. They liked to romp in the woods, play house, of course, swim when possible, and so on. Their mother, Nadine, suggested what they would really enjoy was a playhouse in the bush they could call their own.

Scouring the hills for cedar

Someone guessed they might even want to sleep in such a house. An idea started to take shape in my mind. Wouldn’t it be nice to build a small cedar log structure with a proper roof, door and real windows? I spend the summer scouring the Haliburton hills and found old, very old, Harvey Macintosh with a fence-post cutting business and a small sawmill operation. Perfect. A descendent of Macintosh apple creator, he had stacks of eight-foot cedar posts and 12-foot brace rails. I picked out about 80 posts of the rather small size I needed and a dozen brace rails of similar diameter.

Peeled, sawn on two sides to a uniform thickness of three and one-half inches, another long story, and dried over the winter, they were ready for my construction project to begin the next spring. In the meantime, I had built a solid full one-inch cedar floor in my garage workshop. It was the exact size, nine feet by 11, to fit within the hundred square feet exemption cut-off for a building permit in the county. The floor boards were solidly mounted on four pressure treated four-by-fours. I also prepared a site behind the cedars quite close to the cottage and hauled in a solid crushed gravel base. That was year one.

The logs fall into place

First thing in spring of 1997, after gardening was properly underway, we hauled the floor to the building site. Then, one by one, the logs were put in place with spaces for the door and four windows, all of which were installed as the building went up. The door I constructed of solid cedar planking. The windows were recycled from an old fruit packing shed in B.C. which my dad had demolished many years earlier and I was able to have transported to Toronto. The three grandchildren, all girls, were delighted to climb over the construction site with growing anticipation of the time they had a real house of their own.

To finish off I designed gable ends that looked like logs set vertically and an asphalt shingle clad roof, all specially designed to be air tight and animal proof. One son-in-law, Ian, helped with shingling the roof. Another, Frank, installed the electric service on an underground line from the switch box in the main cottage that Ann had helped me bury under our front lawn. All was in readiness for the interior finishing — but next year.

Design dreams in the wee hours

The workshop was humming in May and June of 1997. During the winter, I had worked out the designs in my head for four sleeping bunks and other fixtures that would be needed. These design sessions usually came upon me in the middle of the night and robbed me of many hours of sleep, just as they had done the previous winter when I had worked out the plans for the bunkie itself. In my mind, I always thought of it as a bunkie. When it was finished, the kids quickly baptised it “The Kids’ Kabin” with two K’s.

With three grandchildren underfoot and a fourth underway, clearly the least number of sleeping bunks required was four. So, the design provided one set of upper and lower bunks on each side of the cabin. All were attached to the wall with hinges so they could be tucked out of the way against the wall when not needed. The ground floor bunks each hid a large roll-out drawer and had additional space on the floor for other storage including a ladder needed to get to the top bunks.

Windows front and back had hinges and screens for fresh, cooling night air. The window on the side facing the cottage gives a good view of the cottage past the cedar tree trunks. Against the blank wall at the foot of the bunks, I built a corner bench along two sides stretching from the end of the bunks around to the small closet in the opposite corner where the door opens in a tight spot between the closet and the bunks on the other side. I made a bookshelf high over the bench and window at the open wall. The drawers are rarely used and the main function of the closet has been to house the potty that is so handy for the younger children.

“Their eyes sparkled…”

The best inspiration I got in my nocturnal mental wanderings was the construction of a collapsible table between the two sets of bunks, reminiscent of dining tables seen typically in travel trailers. Hinged about 12 inches from the wall, when the single but sturdy supporting leg is clapped inward, the table provides a marvellous card or other game playing space between the bunks and is readily collapsed into a small night stand. Four covered foam mattresses, each 30 inches wide and 72 inches long, and voila! The Kids’ Kabin was ready for business.

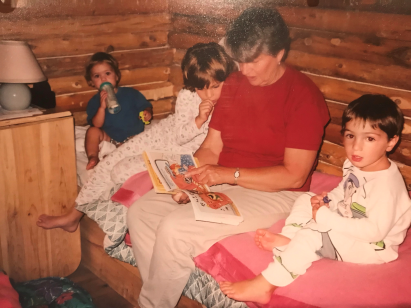

The two oldest grandchildren, Alison and Colleen, arrived on Friday evening of the July 1st long weekend. Their eyes sparkled as they came down the lane and I opened the door to the building I had finished not 10 minutes before. They could hardly wait for bedtime. After some excited chatter which we followed on the baby monitor beamed to the cottage, at the age of only five and three, the girls slept right through to morning. They have only rarely spent a cottage night anywhere else since.

The grandkids keep coming!

Two weeks later, their cousin Anna from New York arrived. And so did Chantal, the daughter of Karen’s partner, Stefan. All four bunks were filled each night!

By the spring of 1999, trouble arrived in the shape of newest grandson, Paul. Where were we to put him? The four bunks were occupied. With some reluctance, I converted the nice bench at the end wall to a bed with a 24 by 60 inch foam mattress. It worked like a charm. This was Paul’s special bed.

But life and laws of fertility being what they are, the next year brought another body to the house in the Kids’ Kabin in the form of Rachel. What to do? I designed a slat frame similar to the bunk beds that could be fit between the two lower bunks. Rachel was delighted to be able to sleep between two big cousins. Problem solved. Six kids housed in a four-bunk cabin.

A few years later, yet another challenge arrived in the firm of Karen and Stefan’s new son, Felix. Suggestions anyone?

Epilogue

Now let’s hear from more of the grandkids…

Rachel, now an engineering student, recalls:

“The cabin had an assortment of blankets — the tiger, the red plaid etc. — and Paul and I would call dibs on the best ones. There was always a rotation of Archie comics that travelled between the cabin and the cottage, and I would hunt down the ones that I hadn’t read yet (that summer) all over the property and bring them back to the cabin.”

“It was always the most fun when the cabin was full of cousins; I would stay up late to listen to all of the gossip.”

Felix, the youngest, and now the tallest, writes: