You may have heard the term “runner’s high.”

One of the pleasures of playing music is finally getting something right, often through practice. Practicing music may not send endorphins coursing through the body, like those giving a feeling of euphoria to a long-distance runner, but it does forge new connections in a musician’s brain. And those can trigger joy in his or her soul.

As I sat down at the Rogers drum kit I had dusted off during the lockdown, I recalled my afternoon practices as a teen in my parents’ basement in Don Mills. I have to give credit to my parents Douglas and Sheila, and my siblings Louise and Andrew, for putting up with the percussive racket coming out of our basement for an hour or so most days.

Practicing sometimes meant the agony of defeat. On one occasion, I was working on studies focusing on “independence” — the ability to separate and free up all four limbs, both on the kit and in the mind.

Despite many attempts, I could not seem to master one of the studies. In a desperate moment, I reared back, stood up, picked up my drum stool, and impaled it in the basement ceiling in frustration.

Damage control

As if waking from a bad dream, I realized what I had done and felt instantly sheepish. I pulled the stool leg out of the ceiling, sat back down on it, and continued my practice. Right after, I camouflaged the damage. Using a pencil to draw dots on a piece of white paper, I simulated the pattern of the ceiling tile. Then I cut it out with scissors and taped my crude circular patch job to the tile. I guess my arts and crafts studies in elementary school had finally paid off. The patch stayed there undetected, although slightly yellowed, until my parents sold the house years later. (Shhhhh! It may still be there today.)

Practice also means the thrill of victory. After getting my Rogers kits set up recently, I started to put together a fall practice agenda. It would be one thing to help get through the continuing covid lockdown, during the long Canadian winter.

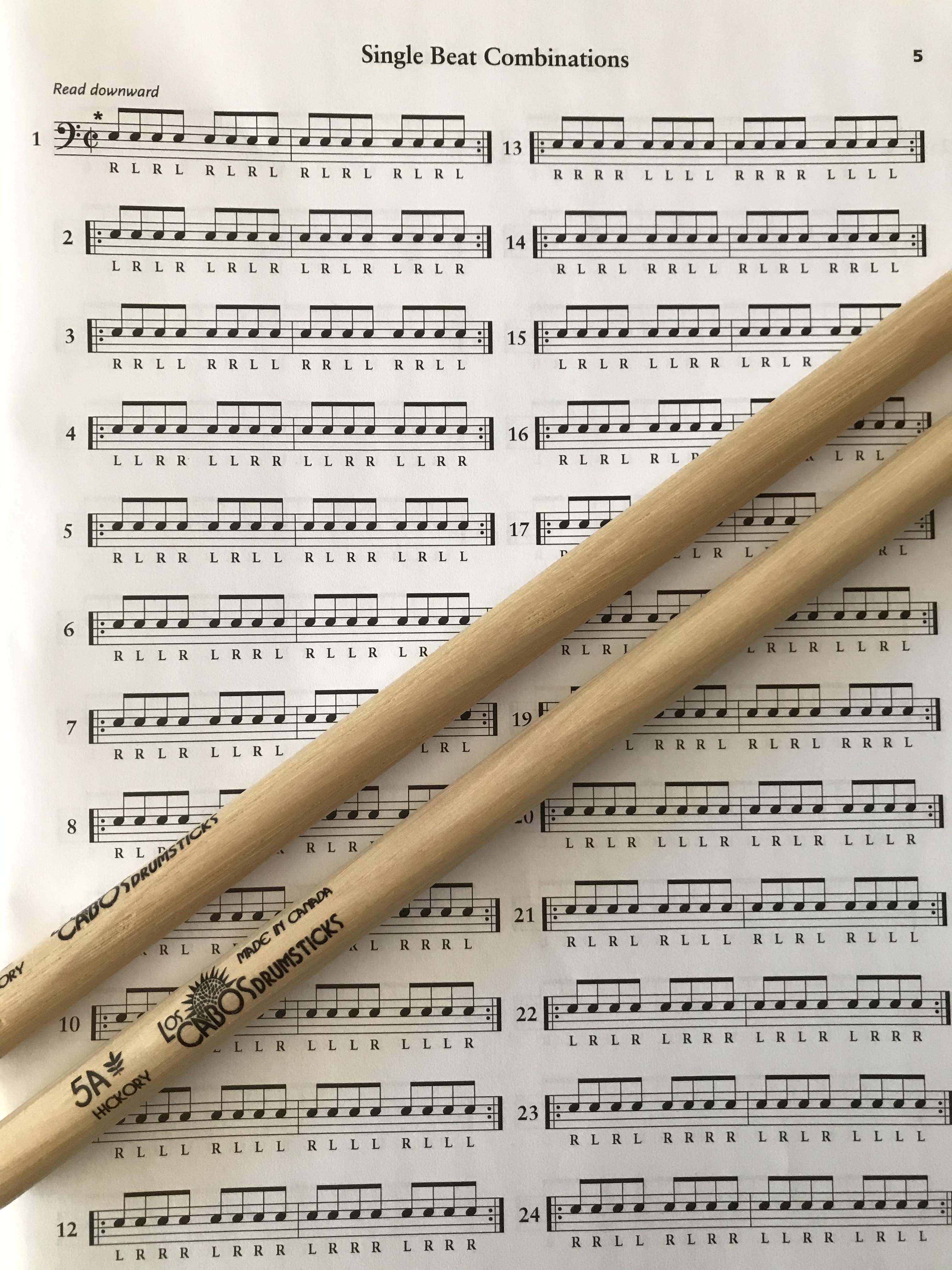

First up was some Stick Control — from the classic 1930s book by George Stone. He focuses on control and liberation of the two hands, through patterns and variations.

Next, I went back over the 18th-century dance suite interpreted for snare drum by Anthony Cirone. I had almost mastered two of the suite’s four studies in the last few months, including a stately Spanish “Sarabande” in 3/4 featuring some lightning-fast passages. But I realized I had glossed over the other two pieces. I dug into the concluding Gigue to polish it up a bit. It would be nice to confidently play the four movements straight through one day.

A segue from snare to set

Those snare studies were actually a neat segue into practicing drum set. With the Sarabande fresh in my mind, I tried to adapt it for the full set, initially bringing in bass drum and high hat. Then, using Cirone’s 4/4 Allemande study as inspiration, I fooled around with a funk beat on the kit. My hands were feeling fluid and I let them drive the beat while my clunkier feet, on bass drum and high hat, filled in some spots with syncopation.

Next door, the neighbors had moved back in after a reno. But Nadine had assured me that when the door was closed to my makeshift practice area in Ali’s old bedroom, the racket was nicely muted.

I made a mental note to speak to the neighbors to apologize and let them know I would never practice after sundown.

Breaking down the shuffle

The thrill of victory came with the last component of this practice session. I had listened to Toto’s classic rock song Roseanna, and found some great YouTube videos breaking down drummer Jeff Porcaro’s fabulous shuffle beat.

The legendary Porcaro made the beat sound easy but it is complex when played at the song’s correct tempo. The YouTube video by Drumeo starts with two hands playing triplets — the right hand on high hat, and the left hand ghosting the second beat of each triplet on the snare. Then to get the backbeat, the left hand has to throw in a combo double backbeat/ghostbeat. For those who read sheet music, the Drumeo video also scores out Porcaro’s beat.

Before even thinking about adding the bass drum, I experimented with the Porcaro shuffle with my left and right hands. It started to click at a slower tempo, so I sped up a bit, feeling good as it started to feel more natural. I kept screwing up, but it felt like some new cerebral connections were being forged.

Not quite a drummer’s high, but I would take it.