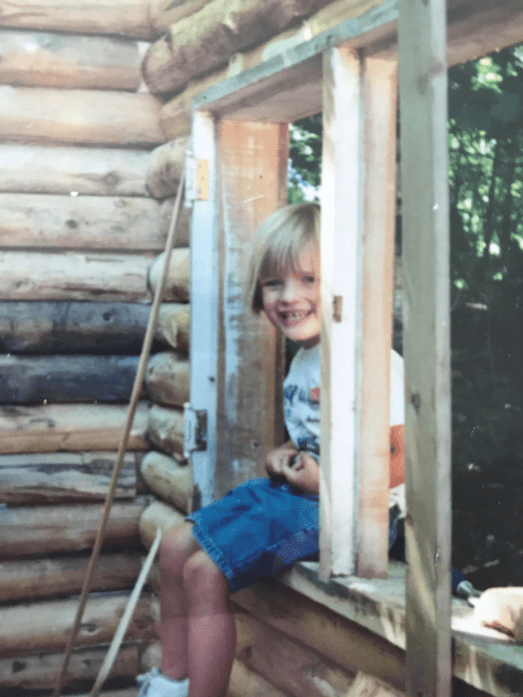

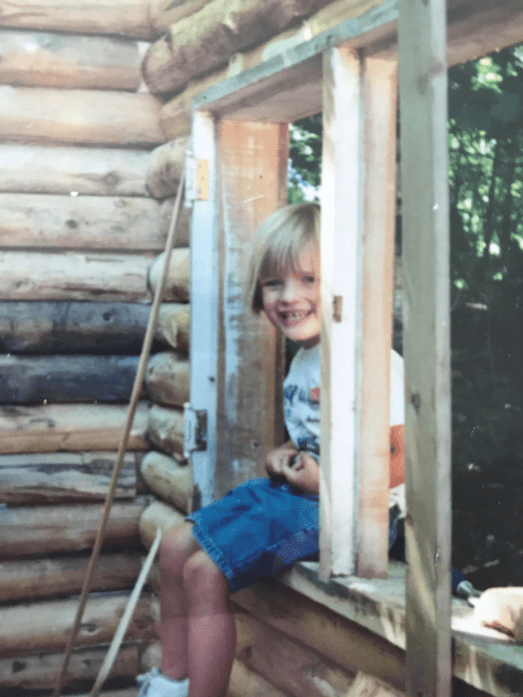

In the mid-90s, Nadine’s parents Ann and Claus were hosting a growing brood of grandchildren at their cottage on Horseshoe Lake. Where to put them all? They needed a tiny cabin movement.

Claus had been looking at a book of cabin designs and, before you knew it, the wheels started turning. He was planning a small 8 x 12-foot log cabin, one that would be built to last and would honour the 150-plus-year homestead cabin that formed the core of their cottage. And at 96 square feet, it would be just small enough not to require a building permit. He ordered cedar logs from a local farmer.

When the logs were delivered, they needed the bark stripped. Claus’s father, Oscar, then into his 90s, was on hand to help.

Cedar and chocolate

Oscar was seated in a lawn chair, wearing a fedora and sports jacket, and a black patch over a wonky eye. In his hands he had a debarking tool and was stripping bark vigorously one log at a time. As a long-time farmer and lumberman, Oscar knew his way around wood. Nadine and I pitched in to help.

From time to time, the kids would come by, and Claus would prompt Oscar about the chocolate. Oscar had brought a shopping bag of at least a dozen bars of fine chocolate along with him, ready to offer up as a treat to the little people when the moment was right.

Claus found a site for the cabin in the woods just across from the main cottage. He set down a gravel base and levelled it up with the help of a few flat stones from the bush.

The cedar logs were stored to dry over winter.

The cabin-building started in earnest the summer of ’97. Claus had the cedar logs milled to four-inch widths so they could be stacked cleanly. As the log walls came up, he notched the ends, knocked in metal spikes, and caulked each log for a tight fit.

Pitching in

Claus had obtained several old wooden windows from his parents’ former place in Grey Creek, B.C., including a two-part solid casement window. They would be a sentimental link to the past, and functional for the future. He took measurements and left space for four windows and a door in the structure. Two windows could be opened for a through breeze.

The wheels were turning on the door too — he had plans for a sturdy but decorative door with diagonal strips that would complete the picture once the structure was built.

Friends and family pitched in. Our brother-in-law Frank worked on the electrical — including supply, lighting and sockets. Nadine and I installed the red shingle roof to match the cottage, working our way around the dormer over the front porch that Claus had added. Nadine figured out the math to get the shingles aligning correctly as we roofed the dormer channel. Claus cut some decorative cedar siding strips to adorn the peak underneath the porch roof.

Meanwhile, Ann and Claus continued to host friends and family who watched the construction unfold. Neighbors dropped by to check progress, offer advice, be inspired, and have a beer.

Finishing touches

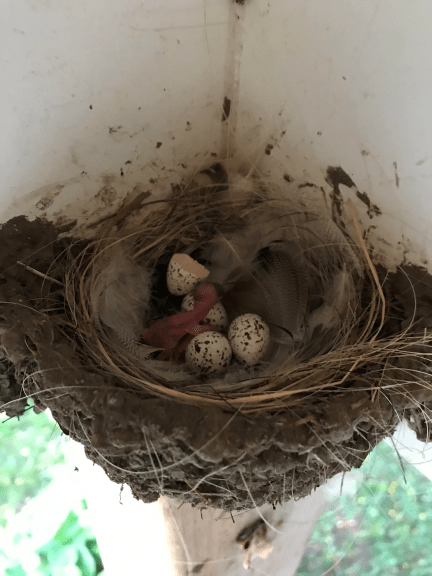

During the third summer, in ’98, Claus finished the interior with several beds. The cabin was nestled nicely into the woods, built solid and ready for grandkids. Nadine and Ann sourced some mattress foam and covers. Linens and pillows were procured for a proper nesting of the interior. Claus asked for contributions for a time capsule that he would hide in a secret spot in the cabin for posterity. As he finished up the cabin interior, he placed a coffee tin inside and asked the kids to put their contributions into the tin time capsule.

Some flat heavy granite steps fronted the cabin porch to the green space outside the cottage. “It’s a 100-year cabin,” Claus declared proudly.

Cabin christening

Ali remembers some unique details of the first sleepovers: “We were given little bowls of Cheerios that we were supposed to eat in the morning to distract us for a little while so the adults could sleep in past 6:30 a.m.!” The kids also played tricks with an electronic baby monitor device. It was installed with good intent to monitor signs of life in the cabin, but the kids got devious, hamming it up over airwaves so that the adults would have to investigate.

Anna recalls the excitement of having her own cabin: “I remember running into the cabin during particularly dramatic rainstorms and listening to the rain and thunder, feeling very cozy but also closer to the storm.”

Cabin for 7

The tiny cabin movement had begun. As more grandkids came along — Chantal, Paul, Rachel, Felix — Claus would continue to add sleeping quarters, turning double bunks into triple bunks with some ingenious carpentry, and adding a small bunk on the west side.

“My favourite was when the middle lower bed was added as the entire lower level was like a big sleepover,” recalls Ali. “The smallest kid had to sleep on the bench bunk, so both Rachel and Felix had to put up with that for awhile.”

“We would play all sorts of games like Ghost Town trying to get everyone settled down but it was tough as everyone was so excited.”

Colleen remembers: “We had quite a book craze with the Goosebumps series. Someone would read aloud and we would discuss what to pick for the “choose your own adventure” challenge. We often had adult visitors who would read a story or two as we were going to bed.”

“As an early-to-bedder I enjoyed many nights hidden away on the cozy top bunk while the chatting continued late into the night between my sister and cousins.

Anna recalls every summer feeling “a bit intimidated to try to get into the top bunks and feeling very proud once I finally got up there!” The kids dressed up the cabin for parties and special occasions: “I remember carrying Rachel into the cabin on a ‘stretcher’ (boogie board) so that she could safely deliver stuffed animals to the ’emergency room’ we created there.”

The cabin also hosted a few adults, and was popular with the children of guests Ann and Claus entertained over the years.

All in the family

Before he passed away, Claus asked that the cabin be kept in the family if possible. With Nadine, he scouted out a possible site in the woods next to our cottage. Ann was preparing to sell the cottage on Horseshoe Lake and kindly offered to move the cabin. Local crane operator Chuck Hopkins obliged, taking the log cabin on a 5K road trip to its new ‘hood.

The tiny cabin movement would continue — on a site nestled in a grove of oak and beech, overlooking a pretty corner of Minden Lake.