Peter Dahl has been connected to the Dahl Forest ever since his parents purchased the former farm in the 1950s. In his lifetime, he’s seen the Dahl Forest undergo a renaissance. Tracts of conifers planted by the Dahl family on depleted farmland are maturing, with a mixed-forest understory emerging beneath. Meanwhile, its natural mixed forests, long ago logged for their massive pine, have regenerated.

In 2009, Peter, with his mother Peggy Dahl and sister Nana McKernan, donated their 500-acre property near Gelert to the Haliburton Highlands Land Trust. Peter and his wife Jan now split their time between a private residence in the Dahl Forest, overlooking the Burnt River, and another home in B.C., close to their son.

With its network of trails, the Dahl Forest is a magical nature reserve, a place to hike, snowshoe, birdwatch… or just get a little fresh air and forest therapy.

As the forest regenerates, its wildlife is returning. Fur-bearing creatures like the beaver and martin are back. Wetlands and their unique wildlife are on the rebound, fueled by many creeks and springs, and cradled by new beaver dams. In winter, the tracks of larger mammals like moose, deer and coyote crisscross the forest.

Peter is also keenly aware of the forest’s human history and the kindred spirits it hosts. The artifacts of homesteader families remain, as does evidence of their toil to clear and farm challenging terrain.

And a river runs through it – the majestic Burnt River, connecting this splendid forest to the greater region, watersheds and wildlife.

On a couple of crisp mornings in February, 2025, Peter stoked the woodstove in the Dahl residence next to the Burnt River, and shared memories and his thoughts about the Dahl Forest’s human and natural history. Following is part 1 of the interview series. For the full story, please visit: https://www.haliburtonlandtrust.ca/2025/04/peter-dahl-interview/

Forest Renaissance

Your family planted more than 100,000 trees on depleted tracts of farmland here. Can you tell us more about this pic of two young tree-planters?

That’s me on the left, with my school friend Bill Szego. Our family lived in Lindsay, and we’d come up to the farm on weekends. In the photo you can see Bill and I seated on a planting machine pulled by a tractor. My dad Eric or a hired hand would have been driving. My dad likely took this photo.

The machine cuts and splits the soil. Bill and I would take turns planting the pine seedlings at intervals measured by a string. The two canted wheels of the machine would then squeeze the soil back together around each new seedling.

Why were the trees planted? Were you ahead of the curve on rewilding?

My Dad’s original intention for planting the trees was to get a cash crop. He was from Sweden, which has a long tradition of managed forests for lumber. In Europe, there was also that mythology about the wild west in North America. He was excited to own a piece of the Canadian wilderness, to have this land as a place to hunt, trap and fish. At the same time, my parents were always open to share the land with others. That idea was also part of his Swedish heritage.

It takes a long time to grow trees for saleable lumber. How did the plans for the Dahl farm change over the years?

Dad lost interest in the lumber cash crop. When we investigated the option further, it wasn’t economically viable. We did do some thinning of the pine plantations but as time went on, we decided to let nature take its course.

Also, for mom, my sister and I, the farm had always been a place to get away to and enjoy. Mom really loved it here. She was born in Guelph and professionally trained as a violinist. She once worked as a music instructor at a girls’ camp in Algonquin Park. I believe that for a city girl, that experience, including the wilderness canoe trips she went on, was important to her love of nature and the outdoors. When my parents were courting, they canoe-tripped extensively. Mom loved the natural world that was part of the Dahl Forest. When my parents divorced in the 1980s, Mom retained ownership of the farm.

Mother nature can be a powerful force over time, if you allow it. What we’ve seen over the years is that the natural forests here are thriving again. That includes some of the hardwood areas as well as the original dominant species of pine returning. In the plantation areas, we’re now seeing some self-thinning of the bigger trees, and a new diverse understory of species like maple, poplar and balsam fir coming up.

How does this affect the wetlands and water courses here?

One of the amazing things is the water table has risen! I’ve recently seen springs pop up in places we’ve never seen before. With an expanded forest canopy and roots, the creeks run longer. The wetland and pond areas are expanding – some large ponds are now small lakes.

What about animal species in the Dahl Forest?

The changes we see here with the forest and wildlife are all connected.

The beavers were trapped around here until about 25 years ago but they’re back now and living in the banks of the Burnt River. We know they’re thriving because we can see beaver families from our window next to the river. They’ve also built at least eight new dams in several of the creek and wetland areas.

Many other creatures of the forest are returning, like mink, fisher and martin. We saw our first martin not too long ago – it caught a squirrel near the house. Moose and deer are prominent here now, along with their predator species including wolves and coyotes.

The change is slow, like the tide. When you see new things, you step back and say: “Wow.” It’s gone from forest to farm and back again.

(Peter in winter 2024/25 next to a tree he planted as a child. Photo by Jan MacLennan)

Why is it important for you to talk about the history of Dahl Forest?

I’m in my mid-70s now. I realize that some of my knowledge – like the location and memories of the homesteads here, and how the place evolved in my lifetime – will be important to share with future generations.

The concept of stewardship is important to me. The oversight and protection of the natural world is ultimately tied to the concept of caring. That means caring for the land, its health, beauty and future. The Dahl Forest now belongs to the community, and its spirit will continue and be cared for.

Mapping the Dahl…

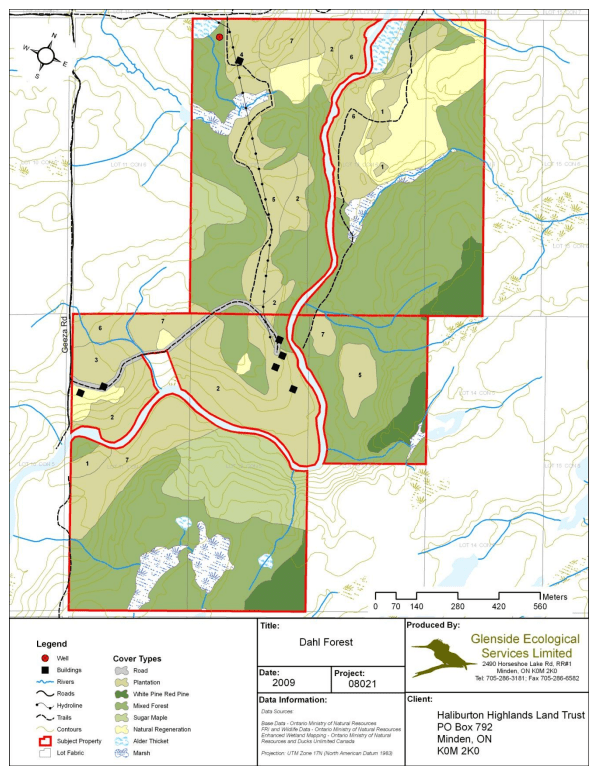

Peter shares a diagram from a detailed ecological report on the Dahl Forest. On the map above, created by Glenside Ecological Services for the Haliburton Highlands Land Trust, you can see some of the reserve’s original natural forests that Peter mentioned. The dark areas shown in the south-east corners of the property, for example, represent mostly natural white and red pine forest, mixed with some red maple and balsam fir. There are also large areas of natural mixed forest comprised of balsam fir, red maple, trembling aspen, basswood, sugar maple, white birch, white spruce and nine other tree species.

The main plantation areas – where the Dahl family planted more than 100,000 conifers – are marked in a lighter colour, such as sections in the central/west area near the main entrance, road and river.

Wetlands shown in the north and south areas of Dahl Forest continue to regenerate with the expanding forest canopy and return of species like the beaver.

*****************************************************

Peter throws another log on the fire to keep the place cozy on a crisp winter day. The thermometer showed minus 27C first this morning. But as the sun comes up to break the chill, a few intrepid hikers have already parked near the entrance to the Dahl Forest on Geeza Road. They’re heading out for a winter walk on the forest’s public trails.

(Update: Some areas of the Dahl Forest were hit hard by the ice storm in April 2025. The land trust is assessing the damage and working to clear the public trails and repair other damage.)