The morning sun lights up fresh snow adorning conifers and old apple trees next to Harold Hart’s home on a country road near the village of Harcourt, Ontario. Harold points to fisher tracks outside his front door, and to poplar stumps indicating local beavers have been busy putting up food for winter.

By modern standards, Harold lives an unconventional life — one that prioritizes basic human needs. He draws cool water from a well, heats his home with a wood stove, and uses a solar system to power his lights, small fridge and DVD machine. In his cold-storage room, he has several bushels of apples from his orchard. Dried apple slices and preserved berries give him fruit throughout the winter. When he stopped driving a few years ago, he would walk to town for his mail, food staples and supplies, or get a lift from a friend nearby. Perhaps his only nod to modern technology is the cellphone he uses to text and speak with friends and family.

But Harold comes by his sustainable life honestly. When he was 10 years old in 1949, his parents moved their young family from the manufacturing centre of Oshawa Ontario to a peaceful 100-acre farm with an apple orchard near Harcourt. They put $300 down and paid the balance of $1,700 on installments of $10 per month.

Now in his 80s, Harold has spent most of his life in the natural world. He made his living as a trapper. Over time, he acquired acreages in the bush to expand his lines and ensure a sustainable wildlife population. One parcel of lands he acquired resides in the Highlands Corridor and consists of about 375 acres, including forests, creeks and wetlands, due south of Harcourt, near Highway 118.

Because he cares about his lands and wildlife, and wants to protect them from future development, Harold signed up last year as a Partner in Conservation with the Haliburton Highlands Land Trust. For his 375-acre parcel, he was able to take advantage of a complimentary forest management plan, and related tax incentive, through a grant received by the Land Trust.

On a sunny day in December, 2025, we met Harold at his country home and drove him to nearby Bancroft to pick up some food supplies. On the way, we stopped for a coffee and found out more about his life and his commitment to conservation.

Can you describe life on the family farm when you arrived there in the late 1940s?

It was subsistence farming. We had a dozen chickens, a cow for milk, a couple of pigs, the odd calf and goat, and a horse for work. There were always apples from the orchard, which we sold by the roadside, stored, and made into sauce and cider. Our garden gave us vegetables to eat fresh in season, and store for winter.

My father Louis could always put a meal on the table with the fishing rod. He would walk to lakes nearby and come home with speckled trout. He had a rod with no reel – I remember him whipping around the line to cast, then reeling it in, hand over hand, when he caught a fish. He had a .22 rifle as well and would bring home some partridge, rabbit and squirrel for dinner.

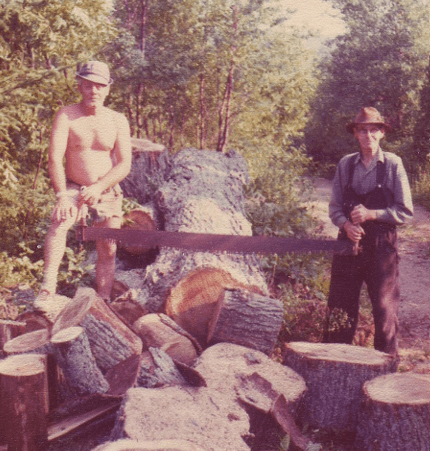

Dad did some lumbering in winter and some roadwork for the township for cash – 60 cents and hour back then.

My mother Alice raised three kids, made our clothes in the early years, cooked, baked, helped my father on the farm, and spent many hours putting away food for the winter – preserving, drying and storing nutritious food to last until spring. Mom also tended a flower garden. Many of her flowers are still blooming to this day in summer – iris, crocus, rose, narcissus and daffodils to name a few. The biggest time consumer for my parents was cutting wood for fuel – especially before we had a chainsaw, horse or vehicle.

Our family didn’t have a big income — but we always had food on the table. My sister, brother and I always had presents for birthdays and Christmas. We didn’t have costly toys but we were creative – like making a fort out of a cardboard box.

We went to a two-room schoolhouse in Wilberforce – one room was Grade 1 to 4; the other was Grade 5 and up. I remember there were only two of us in Grade 5 and I always came second!

When did you learn to hunt and trap?

I started with a bow and arrow for rabbits. When I was 12 years old, I started my first trap line – a few snares around my family’s property. I got mostly squirrels, weasels and mink. Then I would trap the odd beaver, muskrat and fox. I sold my furs to Hudson’s Bay in Winnipeg. I would pack them up and put them in the mail, and they would send a cheque back.

You mentioned that after you finished school, you had worked for the province for several years. Why did you return home to Harcourt?

I was working as an instructor with a Ministry of Corrections program called Project DARE – with the goal of building self-esteem in young offenders. It was based on the philosophy of the Outward Bound program.

On one hand, I enjoyed the work and was making good money. On the other hand, I was getting sick of the workplace politics. Also, I realized that a lot of my income was just flowing out of my hands to taxes and expenses like gas and rent. I felt I was caught in a trap of society and its capitalist system.

At that time, my father gave me some great advice – he told me: “If an average person would work just as hard for himself as he has to for others, he’ll never go wrong in life.”

I realized I could always trap. I had the skills to trap and handle furs. To go along with my family’s 100 acres, I knew I needed more land to be able to trap sustainably. I scouted some bush acreage at reasonable prices and started to purchase some in the mid-1970s.

I transitioned from my government job into a more self-sufficient lifestyle. I could reduce my expenses and make some income with the fur harvesting.

How were things for you in your first few years back in Harcourt?

The Ontario Trappers Association came along and gave some competition to the Bay and better prices for trappers. Fur prices increased. A fox pelt that I used to get 50 cents for was paying a hundred and thirty dollars. A beaver pelt worth two dollars had gone up to a hundred and forty dollars.

So I could get by – I made about $3,000 in my first year or two. By living off the land, and living economically, I was doing well. I gradually bought more land and in some cases was able to resell it later.

What were some of your principles for sustainable fur harvesting and farming?

I was an efficient trapper – while I owned a snowmachine, I chose to snowshoe or walk into most of my lines. As well, I could process the furs in the bush and walk out with them. My biggest line was about 40 traps, maybe two miles long. I would be in there for a day and walk out.

Trapping sustainably also means rotating your lines, and paying attention to the wildlife populations. For example: What’s the main food for a beaver? It’s poplar. You keep an eye on the territory and see where beaver populations are doing well, what poplar sources they have. In the offseason, I have done a lot of culling of conifers around ponds to allow the poplar trees to regrow for the beaver population. You want the wildlife populations to be stable or growing.

It’s the same in the garden – you can’t just take, you have to put back. How did I grow a 50-pound squash? By paying attention to the soil. By using compost and finding natural ways to put nitrogen, phosphorus and potassium back into the soil for the next crops. And in the apple orchard, you take care of the soil and protect the trees.

You treat the land as something you care about and are passing on to somebody. I also want to protect my land from unhealthy forms of development that are spreading around the province. I’m not against development, but some forms are not sustainable.

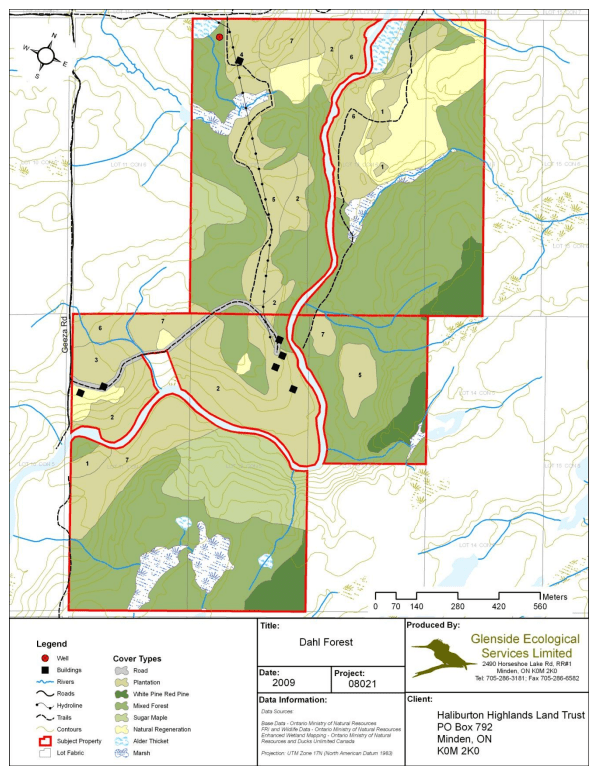

Biologist Paul Heaven did a comprehensive assessment and forest management plan for your 375 acres on behalf of the land trust. It’s a detailed report showing the forests, wetlands, rocky barrens and wildlife on your lands – also your trapper’s cabins and the trails you’ve made over the years. Paul found species such as deer, moose, red fox, eastern wolf, black bear, amphibians, many bird species, as well as diverse tree and plant species.

What’s it like to look at the maps and observations in the plan for your property?

I know it up here (pointing to his head) but it was fun to look at the maps and to speak with Paul. For example, we texted back and forth about a cranberry bog. I remembered it, and I hiked back there recently and discovered another spot where I picked a quart of cranberries. I texted Paul and told him about the harvest and let him know I would be staying there in the bush for a week or so. He texted me back and said he was jealous!

Dutchmen’s Breeches are one of many diverse plant species on Harold’s acreage.

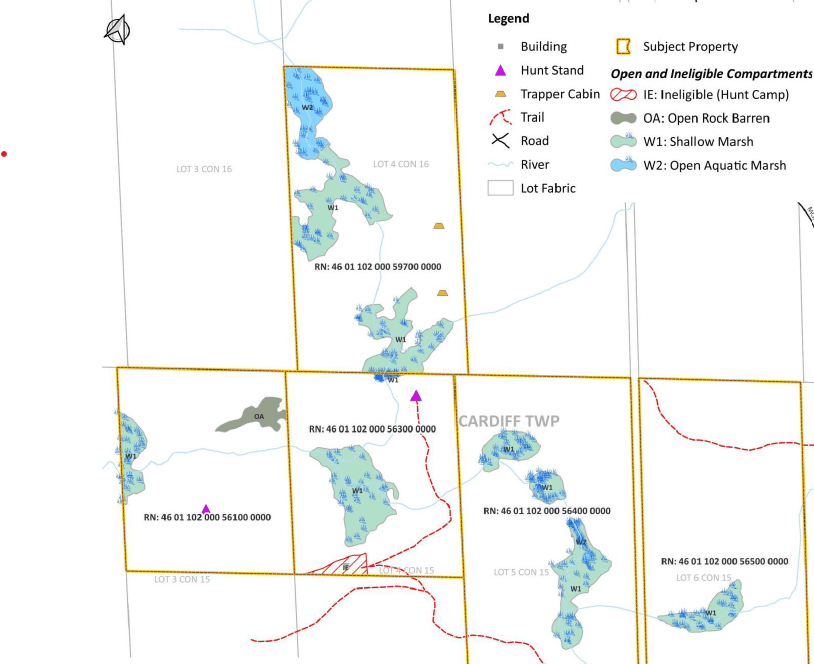

Portion of a map of Harold’s five adjoining properties of forests, wetlands and rocky barrens totaling 375 acres.

You became a Partner in Conservation with the Land Trust last year. There are currently more than 60 partners representing over 10,000 acres — and the program’s now open to any landowner in Haliburton County.

What would you say to someone who might be thinking about becoming a Partner in Conservation?

Each person would see the benefits differently. You are helping with research about the forest and wildlife corridor. There’s a tax benefit from the managed forest program. You get a long-term plan and support to manage your land sustainably.

If you care about preserving your land, it’s worth considering.

Back from our trip to Bancroft, we help Harold bring in a large box of oatmeal and tub of beans from the whole food store. In his 80s, he’s slowing down a bit and so purchases a few more staples. Today, he’s stocking up for maple syrup season next March and April, when he will feed some friends who help with the operation of tapping trees, gathering and boiling sap.

Before saying farewell, we stop to chat in the sunshine outside the stone house he built with mostly local materials in the late 1960s, just down the road from his parents’ farm.

Right next to Harold’s home are some mature apple trees, one with a ladder resting in it. Harold admits he rarely goes up the ladder anymore, but he’s proud of his trees. One is a Wolf River variety – producing a fine cooking apple. Many years ago, he had taken a branch from a Wolf River tree down the road and grafted it to rootstock here. It took him a few years of failed attempts before he matched up the graft to the right rootstock, but the result is a solid producer of apples for his cellar. To his taste, it’s the sweetest Wolf River around.

You’d think it’d be tough to grow apple trees in this area with its cold winters. But with the right touch and stewardship, Harold has nurtured not only apple trees but also pear, cherry, and many varieties of plum, not to mention grapes and berries.

His is an unconventional life that goes well beyond self-sufficiency — to a richness of experience and stewardship of the natural world.

A sustainable life.

Article and interview by volunteer Ian Kinross.

Photos by Ian Kinross, Rick Whitteker and Paul Heaven.

For more information on the Haliburton Highlands Land Trust and its Partners in Conservation Program: please visit: https://www.haliburtonlandtrust.ca/

Additional recommendations from Harold Hart:

- Living the Good Life – a book by Helen and Scott Nearing about their self-sufficient homesteading project in Vermont.

- Fit for Life – a book by Harvey and Marilyn Diamond advocating a diet prioritizing fruits and vegetables.

- Last but not least, Harold recommends that property owners in the Haliburton region consider the Partners in Conservation Program: “Each person can do their part to save our natural world and planet.”