Indigenous peoples and pioneering homesteaders are part of the human history of the Dahl Forest, near Gelert, Ontario. Artifacts signal the presence of indigenous peoples who long ago used the Burnt River as a major travel route. While the homesteaders are long gone, evidence of their toil to farm this rugged land remains.

Peter Dahl was a young boy when his parents purchased the Dahl Forest lands in the 1950s. In 2009, Peter and his family donated the former 500-acre farm to the Haliburton Highlands Land Trust. We asked Peter to share his memories of the Dahl Forest’s human history.

The survey done of Dahl Forest for the land trust showed the remnants of the Strafford homestead in the northwest corner of the property. The Straffords had immigrated from Berkshire, England in the 1870s to accept a “free-grant” farmstead here. What do you remember about this homestead?

The Strafford’s log house still stood when our family purchased the land — I used to play in there as a kid. There was an attic accessed by a ladder from outside. I recall going up there and seeing old newspapers used for insulation. One of them had a headline about the Czar of Russia, so it must have been placed there around the turn of the century.

Inside, I recall a pump organ – the kind of organ you had to pump your feet to play.

Mr. Strafford had been integral in building the S.S. #6 school that still stands nearby, next to Geeza Road. We know that he was a school trustee and a lay preacher, in addition to farming.

The land trust plaque near the foundation of the old homestead says that the Straffords left for Nebraska in the 1890s, after about 20 years trying to make a go of it. What was life was like for homesteaders like them?

They were given free land — but the labour to settle it, clear it and farm it was extreme. On all the homesteads here at Dahl Forest, you can see evidence of the human toil to clear stone, for example.

As a kid, I saw these massive stone piles and long stone fences that the homesteaders had built up while clearing their fields for cattle and crops. Some of the bigger stones must weigh a ton or more.

After all of the back-breaking work they put into it, it must have been a terribly hard decision for a family like the Straffords to walk away from their home and farm here. Nebraska would offer them more fertile soil and a better chance.

Let’s continue our tour of your homestead memories. Were there other pioneers in this north-west section of what is now the Dahl Forest?

The Miles homestead was near what’s now the north gate of the Dahl Forest, east of the Staffords. Almost nothing of it remains today.

When I was young, our family came upon a children’s gravesite towards the Miles homestead. I remember a circular picket fence that sat in a field of rolling grass. Some lilacs had been planted in the middle. There were no markers left, but it was clear that it had been used as a burial site. The site used to appear on aerial photographs as a black dot.

Nobody knows which children lie there. We thought it could be children of either the Miles or Stafford families, or both.

Looking back, we know that the many pioneer families lost children to diseases caused by poor nutrition, polluted well water and weather extremes. And doctors were hard to come by. Pioneer life was even tougher when it came to the survival of children.

You mentioned that when your family purchased this land in the 1950s, you would come up from Lindsay and stay in the former homestead of the Bowhey, then Schrader families. This was near the main entrance to today’s Dahl Forest on Geeza Road.

My dad renovated the Schrader house into a recreational cottage when he first purchased the property in 1955. That was our place until the current cottage, which is now our house, was built in 1976 next to the river. The original homestead was demolished by the land trust for safety reasons a few years ago as it was deteriorating badly.

Were the Schraders still farming when your family purchased the property?

Yes, the Schrader family had still been raising some cattle there. The cattle ranged freely around the hills around the river; I remember hearing their bells in the distance. The cattle wintered in the barn near the homestead.

The barn was in good shape, and I played in there as a kid. There were piles of hay and straw and ropes to haul it in. There was an old cutter in there — a horse-drawn sled for trips to town in winter. And the body of a Ford Model A car. My dad didn’t need the barn, so he had it torn down and kept the utility garage nearby. You can still see the stone foundation of that barn next to one of the Dahl Forest trails.

Bowhey/Schrader barn in the 1950s.

I see you’ve kept and displayed some of the farming implements from the barn. I’m sure each one has a story to tell.

The cross-cut saw was used to saw logs by hand before they were split. The cow bells were to keep track of the cattle that ranged freely on both sides of the river. The scythe was used to take hay by hand. Looking at the whiffle-tree harness, you can visualize a pair of horses hauling lumber in winter.

You can imagine a totally different world – almost third-world conditions with no electrical power, plumbing or telephone, no cars, and a tremendous effort to survive. The well was about 50 metres from the house, with water carried by bucket.

How did things change for the homesteaders in this area over the years?

Besides the cattle and some crops, they also looked to make some cash selling gravel and wood-cutting.

But it was a hardscrabble life. People needed steady income. Gren Schrader went to work at the CNR as a telegraphist and railway manager. Likewise, most of younger generation around here heard about good jobs elsewhere – I know some of them went to work for GM in Oshawa for example, rather than stay on the farm.

Gren and his son Rob preserved a lot of history about the Dahl Forest and this area and its people. Rob Schrader is a friend of mine and still visits a cabin he owns further along Geeza Road.

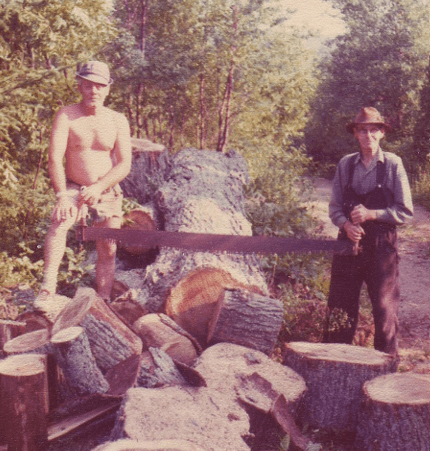

Gren Schrader, left, helps Raymond Geeza saw logs for firewood in 1974. Gren was 44 at the time of the photo; his cousin Raymond was 89 and, as Gren recalled, had more stamina with the cross-cut saw! (Photo courtesy of Schrader family.)

Are you aware of any history of indigenous peoples in the area of Dahl Forest?

My understanding is that the Burnt River was a major travel and trade route for indigenous peoples between lakes in the Haliburton area and the Kawarthas. Almost three kilometers of this river runs through the Dahl Forest.

When I was a child, Tommy Hoyle, whose family lived just north of the Dahl farm, gave my dad a stone axe head that he had found near the river.

When Jan and I were canoeing down the Burnt River towards Kinmount, I found a marvelous stone pipe lying on the bottom of the river about a kilometer or two downstream of the Dahl Forest. It was about six inches long, with the bowl canted forward a bit. It likely had washed out of the riverbank; it was a stroke of luck that I found it.

I had it examined at Wilfred Laurier University’s archeology department and a scientist there appraised it as being pre-contact, from the Algonquin culture. The pipe is now in the Haliburton museum.

Stone pipe from Algonquin culture found by Peter Dahl near Dahl Forest. It is part of an exhibit of indigenous artifacts at the Haliburton’s Museum. The ridges in foreground were likely once decorated with brightly coloured inlays, and the bowl of the pipe may have had a wooden figure attached, such as a bird’s head. The museum offers a report by David Beaucage Johnson on the history of indigenous settlement in Haliburton County. You can find it at this link: //database.ulinks.ca/items/show/4842

For the complete interviews with Peter including the Dahl Forest renaissance and connection to the Burnt River, please visit the Haliburton Highlands Land Trust website here:

https://www.haliburtonlandtrust.ca/2025/04/peter-dahl-interview/