As a hike leader in the Haliburton area, Rob Halupka gets a kick out of helping others experience nature. “My role is being a conduit to help them discover the great outdoors,” says the retired engineer, who’s worked in the mining and financial sectors. “One of my rewards is to see things fresh through their eyes.”

Above: Rob at left with hikers on a Ganaraska Hiking Trail event in May, 2024

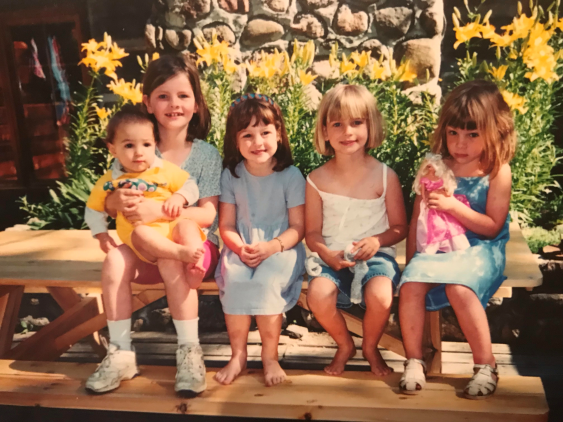

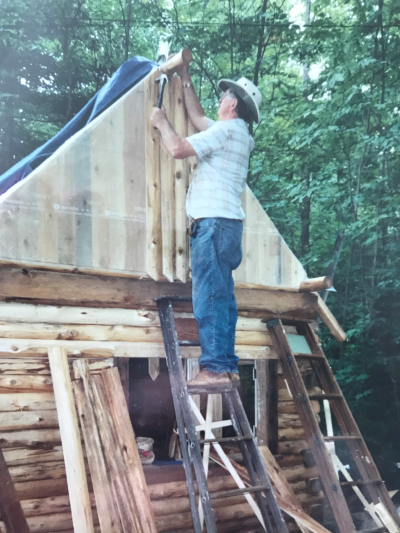

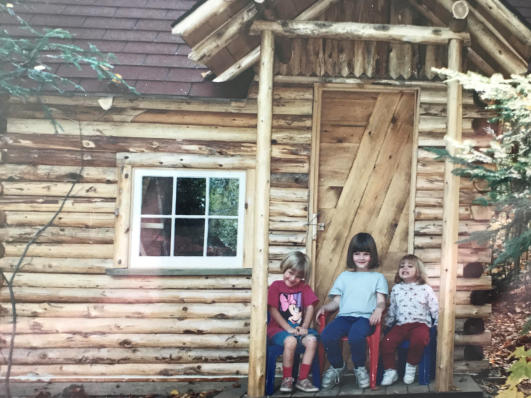

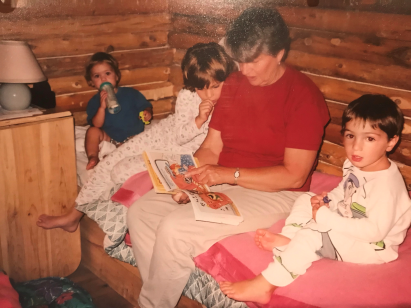

I know first-hand Rob’s experience and skills in the wilderness. When our kids were young, we joined Rob, his wife Jacquie and their children Madde and Emma on some epic canoe trips to Ontario destinations like northwest Algonquin Park. With another family of four, our friends the Finleys, we 12 paddled, portaged, swam and cooked up some feasts over the campfire. I recall Rob venturing off into the woods with a small hatchet and knife, and returning to set up a wooden tripod for our stew, complete with a hook on an adjustable wire that could raise and lower the pot over the fire as required. He also helped us prepare with detailed checklists for the trip that always ended with these two items: unmentionables and a rubber chicken.

Fast forward 20-plus years and Rob is a certified hike leader and president of the Wilderness Club — one of nine trail sections of Ontario’s Ganaraska Hiking Trail Association. The rugged section of trails Rob heads up is definitely off-grid. It includes 72 kilometres of trails winding through rivers, lakes, Canadian Shield, woodland and wetland, most of it within Queen Elizabeth II Wildlands Provincial Park. The legendary “cross-over” hike typically takes three days — including two nights of overnight camping.

I invited Rob, Jacquie and their faithful hound Mungo to join me recently for a hike to one of my favourite spots, Kinross Creek, back in the bush about a 45-minute walk from our cottage. Rob showed me a neat app called Avenza that I used to track the hike. The four of us took a little rest near a tiny lake, then ventured back to Kinross Creek where four frogs scattered after Mungo hopped in the water to cool off.

Afterwards, I spoke more to Rob about hiking, the great outdoors, and his impressions of Kinross Creek. In future, I look forward to interviewing Jacquie for her take on interpreting the great outdoors through art.

You lead hiking groups that may include veteran hikers but also newbies. What do they get out of this experience?

Some of our new hikers are also new Canadians. They want to experience the beauty of the Canadian wilderness and wildlife but may not have the skills, knowledge or equipment to do it. They may have certain fears — like a fear of bears or snakes.

They may not know how to do it, but they know they want to do it!

Yesterday on a trail-clearing event we had hikers who had immigrated to Canada from Iran, United Arab Emirates, England, Russia, India and Vietnam. My role is being a conduit for them to experience the outdoors, and one of my rewards is to see things fresh through their eyes.

We also have some veteran hikers. One woman, in her 70s, has hiked the entire Appalachian Trail (more than 2,000 miles) in the U.S. She’s exceptionally fit and well prepared with ultralight gear and the right clothing. She is testing her stamina and knowledge, so it is a different kind of reward for her.

What responsibilities do you take on as a hike leader? How do you prepare?

Leading up to a hike, I ask a lot of questions. I want to know where each person is in terms of their experience. Also whether there are health issues I should know about. In some cases it is a reality check. If we are looking at a full day hike, or multi-day hike, through some areas that may not have cell phone service or road access, they need to know exactly what they are getting into. Each person also gets a checklist of equipment and supplies.

So there is individual preparation but we also look at preparation as a group — for example, to make sure that if one person has forgotten something, we can still function as a group. A simple example is ensuring we have a water filter and enough stoves for the group. We also look at weather conditions and limit the size of the group for safety.

The hike leaders have to be trained. I have my Certified Hike Leader — CHL — accreditation from Hike Ontario. The training involves fundamentals and simulated emergencies and how to deal with them. As well, I regularly update my first-aid training.

For longer hikes, we have a leader and a sweep — two experienced people responsible for the group. Between us, we want to keep the group safe and to avoid the slinky effect — we do not want the hike group to get stretched too far.

Can you describe a challenging situation on a hike and how you addressed it?

When you are into a multi-day hike, there is a point of no-return. You are all in.

On our cross-over hike from Devil’s Lake (south of Minden, Ontario) to Victoria Falls (north of Sebright, Ontario), we had a group of women who were veteran day hikers but had not done overnight trips. We carried 30-pound packs with food and gear. On our first day, my experienced partner Vlad was the guide, while I brought up the rear as sweep. Vlad became concerned that our group was too slow. Everyone was enjoying the hike, but Vlad quickly realized we were not going to reach our campsite in good time. He had to get serious and hustle the group and they were taken aback at first. I played more of the good cop, encouraging everyone. We were able to speed up and thankfully make camp that night.

They forgave Vlad later — they knew there was a good reason he was a bit brusque earlier in the day. We also realized not all hikers had good sleeping bags. During the day, the temperature was fine but overnight we were getting some frost. So as a group we were able to rustle up and share some gear so our hikers could stay warm.

Hiking can be a serious business but you also address the lighter side.

Our hikers want to have fun and experience wildlife and nature. This is not the marine corps!

There is an education component but I try to treat that in a fun way. I’ve been known to ask skill-testing questions along a hike. When a hiker gets it right, they get a little plastic model dinosaur as a prize. We take a break at a little enclave of rocks and moss. I explain that 66 million years ago, most dinosaurs were killed off in a mass extinction — except for this little spot on our hike. The hikers get a kick out of finding what I call Jurassic Parkette — a collection of little plastic dinosaurs in the wilderness. The prize-winners add their dinosaurs to the montage.

Hikers have a lot of questions about the natural world. On a recent hike we found some moose tracks and ended up having a great chat about animal poop and its different qualities — like the difference between small dry deer pellets and the messy poop of a bear who has feasted on berries. I was also able to explain the odd behaviour of a grouse that was apparently harassing our group, but was actually protecting her chicks.

On breaks, I’ve also been known to recite Robert Service poetry like the Cremation of Sam McGee — and tell bad jokes.

Jacquie and Rob near Kinross Creek

When we visited Kinross Creek, you showed me how to use the Avenza app to map out the hike. Is this a tool you use on your guided hikes?

Avenza is great to document a hike — the route, the distance, the time it takes, and points of interest along the way. It can also help to lay out and document the best trail. Of course, it is also important to use physical markers. I use coloured tape, and also am constantly snipping branches and removing obstacles. For example, we can document a main route using orange and yellow tape, and then mark some alternative routes with blue and yellow markers. So the combination of the digital app and the trail markings are important for navigation.

Near Kinross Creek we came across some massive stone piles and abandoned farm buildings.

We saw evidence of some of the history of the early farmers in that area. My first reaction was — somebody broke their back moving all those stones to try to establish a farm! They were likely given free land but had to work to develop it in a very challenging topography and climate. Some of them eked out a living for awhile but could not sustain it and had to abandon their farms, unfortunately.

Most people on my hikes are not from this area and have questions about history and the natural world here. So I have done some research on the Haliburton area. I also use an app called Merlin to track the bird life on our hikes. When we were at Kinross Creek, I heard a Rose-Breasted Grosbeak, and the app also identified an Indigo Bunting, which is a gorgeous blue bird returning here after migration. If you combine the app with a pair of binoculars, you can see many birds along the way.

Rob and Mungo, back in the bush

Over the past year, you have taken on many different hikes with groups including Hike Haliburton and of course the Ganaraska group. What is the reward for you?

I used to do a lot of hiking and canoeing either solo or with family, which is always fun. Leading group hikes now, with so many different participants, I can give them some guidance and a little boost.

Seeing nature through their eyes too — that is a big reward.

For more information, please visit the Ganaraska Hiking Trail Association — Wilderness Club Facebook page. Or you can visit the Ganaraska Hiking Trail Association website here: https://ganaraska-hiking-trail.org/

My first frog at Kinross Creek. Cutie!